What Is Aesthetics Or Alamakara Shastra?

Sanskrit aesthetic theory (alamkara sastra) developed in India as a way to explain the aim of play and poetry, and is known as alamkara (ornamentation/beauty).

Early theoreticians interpreted alamkara to mean both beauty and beauty achieved via adornment.

In the first definition, alamkara (virtues/qualities) is innate, but in the second, it is created by the use of words or theatrical gesture to achieve a certain impression.

However, as with Anandavardhana's theoretical works, a philosophical change happened in this understanding of the connection of alamkara to the guna (c. ninth century).

He stated that even someone with minimal technical expertise

but an intuitive sensibility may be brought to an aesthetic experience

(Krishnamoorthy 1979: 123–25).

He did not dispute the importance of alamkara and guna to aesthetic experience.

This, of course, implies that there is something intrinsic

in the work of art, whether it poetry, theater, or painting, that transcends

its mechanics.

What Is The Theory of Rasa?

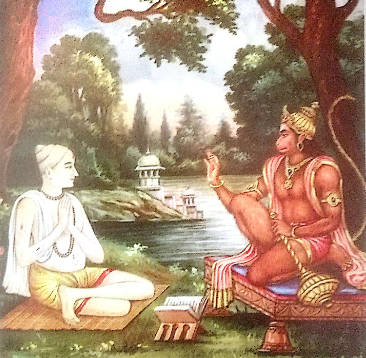

The idea of rasa, which first appears in the sixth chapter of the second-century Sanskrit dramaturgical handbook Natyasastra, is perhaps the most prevalent and influential Indian aesthetic philosophy.

The term rasa literally means "taste" or "appreciation."

In terms of aesthetics, rasa is the consequence of a

careful balance of stimulus (vibhava), automatic response (anubhava), and

intentional reaction (anubhava) (vyab hicaribhava).

Rasa is likened to the cooking process, in which the

components, each different in their own way, come together to create a singular

flavor.

The flavor is the rasa aesthetic experience, the components

are the different bhavas (emotions), and the person who can experience rasa is

called as a rasika.

The Natyasastra lists eight basic rasas, each with its own set of bhavas (emotions).

To put it another way, if bhava is the feeling, rasa may be

thought of as the aesthetic experience of that emotion.

The eight rasas are listed here, together with their corresponding sthayi bhavas (permanent/stable emotions) (Rangacharya 1986: 38–39).

- Rasa (Bhava)

- Srngara (erotic)

- Rati (desire)

- Hasya (comic),

- Hasaaaaaaaaaa (laughter)

- Karuna(compassion)

- Soka (grief)

- Raudra (fearsome)

- Krodha (anger)

- Vira (heroic)

- Utsaha (energy)

- Bhayanaka (fearsome)

- Bhaya (fear)

- Bibhatsa (loathsome)

- Jugupsa(disgust)

- Adbhuta (wonder)

- Vismaya (astonishment)

When rasa theory is applied to an Advaitic philosophical

philosophy, a crucial ninth rasa, Santa (tranquility), is introduced.

It was just recently inserted into the Natyasastra text,

and it is commonly attributed to the eighth-century philosopher Udbhata.

Santa, on the other hand, is not merely another rasa; it is the basic state of thought from which all other rasas are derived (Krishna moorthy 1979: 206–10).

Another key notion is sadharanikarana (universalizing emotion), which was first proposed by Bhatta Nayaka (ninth century) and further expanded by Abhinavagupta (tenth century) in his commentary on the Natyasastra, Abhinavabharati.

Abhinavagupta is largely speaking in the context of Natya

when he comments on Bhatta Nayaka's notion offspring sadharanikarana

(drama).

Natya refers to both the text itself and the actual

performing that gives the text meaning.

Unlike emotions that one encounters in reality, which link

one to the world, the emotions that occur as a reaction to art (or art-like

experiences) lead readers/audience to transcend their subjectivity and

individuality.

According to Abhinavagupta, a rasa experience is impossible without sadharanikaran. (Krishnamoorthy 1979: 214–15), and hence aesthetic experience correlates to the yogin's mystical bliss.

What Is Bhakti Rasa?

The rise of bhakti as a significant literary and theological movement has led to its classification as a rasa.

Bhakti rasa became the dominating and preeminent metaphor of

divine experience, particularly within the intellectual circles of Vallabha,

Caitanya, and the Gosvamis.

Bhakti was originally intended as a bhava, not a rasa.

However, two thirteenth-century interpreters on the

Bhagavata Puran, Vopadeva and Hemadri, not only promoted bhakti as a rasa, but

even replaced Santa to argue for it as the rasa par excellence.

Instead of Santa, the other nine rasas are now variations of

bhakti.

The sensation of happiness created by listening, reading,

and participating in some manner in the exploits of God and his followers is a

basic description of bhakti rasa.

Other Vaisnava schools, especially Caitanya, Vallabha, and the Goswamis, have significant discrepancies in the formulation of bhakti rasa, and these schools have significant disparities among themselves.

Sringara or madhurya (sweetness) was the most effective

medium for approximating the ecstasy of mystical connection for them (Krishnamoorthy 1979: 198–201).

What Is Aesthetic theory in Tamil Literature And Philosophy?

The complimentary ideas of interior/exterior, public/private worlds, and inner and outer in Tamil aesthetic theory are referred to as akam (inner) and puram(outer).

It grew up alongside what is known as the Sangam/Cankam era of

poetry (first to third centuries).

Puram poetry represented monarchs, battle, and ethics, but

akam poetry dealt with love, desire, and yearning.

The universe and emotions were divided into five landscapes (tinai) in the akam world, each of which symbolized a stage in the growth of love.

The hero, heroine, her friend, his friend, and so on were

all anonymous and archetypal in the akam world.

The pur.am poetry, on the other hand, included named

kings, 'real' events, and bards touring the countryside in quest of a wealthy

patron.

Cankam poetry's aesthetic norms had a big effect on emerging Tamil bhakti poetry (sixth to ninth centuries).

These traveling poets stole the structures and genres of the

previous literary era to convey a new religious sensibility.

For some ways, bhakti religion brought in a new literary

form.

Although identifying the hero (god) and heroine (the poet in

his/her persona) broke a basic aesthetic value, the bhakti poem used the form

of the nameless hero and heroine of the akam poems.

In addition, the poets elevated the god to the status of

monarch in their newly created pur.am poetry, transforming the bard-royal

connection into that of the devotee and his chosen deity.

The shattering of the invisible and impassable barrier

between the poet and the imagined poetic environment was perhaps the most

profound aesthetic change of these new poems.

By identifying their characters and personalizing their

poetic narratives, the new bhakti poems brought the listener into the poem in a

manner that the antecedent akam and pur.am poems could not (Selby 2000: 26–35).

See also:

Abhinavagupta; Advaita; Bhakti; Caitanya; Drama; Gun.as; Kashmiri Saivism; Languages; Poetry; Puranas; Sanskrit; Vaisnavism; Vallabha; Yogı Archana Venkatesan

References And Further reading:

- Krishnamoorthy, K. 1979. Studies in Indian Aesthetics and Criticism. Mysore: Mysore Printing and Publishing House.

- Rangacharya, Adya. 1986. Natyasastra (English Translation with Critical Notes). Bangalore: IBH Prakashana.

- Selby, Martha Ann. 2000. Grow Long Blessed Night: Love Poems from Classical India. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Tapasyananda, Swami. 1990. Bhakti Schools of Vedanta: Lives and Philosophies of Ramanuja, Nimbarka, Madhava, Vallabha and Caitanya. Madras: Sri Ramakrishna Math.